- Prosecution claims Assange won’t face isolation in U.S. prison

- U.S. attempts to undermine renowned psychiatrist’s testimony

- Defense responds; judge preferred Kopelman

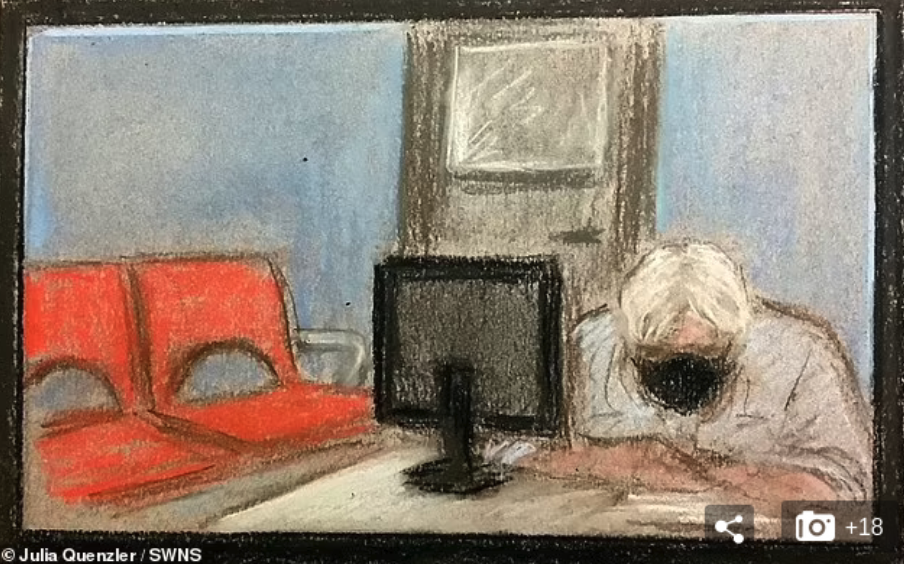

Assange too unwell to view proceedings remotely

Julian Assange’s extradition appeal hearing, which will turn in part on determinations about his health and risk of suicide, commenced with the news that Julian was too ill to even follow the proceedings by remote videolink from Belmarsh prison. Julian did enter the viewing box about midway through the morning’s session, but he appeared thin and unwell, and he could be seen leaving the room about an hour later.

Assange’s extradition was denied in January of this year when District Judge Vanessa Baraitser ruled that ordering his extradition would put him at such high risk of suicide so as to be “oppressive.” The U.S. is appealing that ruling to the UK’s High Court on the grounds that, it argues, the judge misapplied evidence as to Assange’s mental health, and the U.S. government can assure the court that Assange wouldn’t be held under the worst and most isolating conditions if sentenced to a U.S. prison.

Prosecution claims Assange won’t face isolation in U.S. prison

As the appealing party, the U.S. government argued first, led by James Lewis QC. Lewis broke up up its objections to each aspect of the judge’s finding — whether Assange’s mental health condition puts him at high risk of suicide, his personal capacity to resist that impulse, how prospective treatment affects that risk level. He began with the so-called “assurances” that Assange wouldn’t be placed in ADX Florence, the U.S.’s highest-security prison designed specifically to isolate its inmates, and that he wouldn’t be subject to Special Administrative Measures (SAMs), which are applied, often in national security cases, to even further restrict an inmate’s communication with the outside world. The U.S. worked to restrict all of the defense’s objections regarding prison conditions to ADX Florence and SAMs, attempting to narrow its burden of proof by arguing that if ADX Florence and SAMs were removed from the equation, Judge Baraitser would have ruled to extradite Assange.

Amnesty International has warned that assurances Assange wouldn’t be placed in ADX Florence and that SAMs wouldn’t be imposed are “inherently unreliable,” as they contain the crucial caveat that the U.S. can change its mind whenever it chooses, if it determines that Assange has done something to warrant isolation or SAMs. Lewis admitted that these assurances are indeed “conditional,” but he said that they must be, “otherwise it would give him a blank check to do whatever he’d like.”

Lewis argued against the defense’s contention that Assange would likely face solitary confinement in pre-trial detention by claiming that Assange would be allowed to visit with his lawyers whenever he would like. (Note that even in detention in the UK, Assange has gone for stretches of several months without being able to communicate with his legal team.) He also floated the possibility that Assange might not be convicted at all, despite the fact that more than 90% of U.S. federal cases result in guilty verdicts, and Assange would be tried in the U.S.’s harshest district, EDVA (a district that CIA whistleblower John Kiriakou, who has been convicted under the same Espionage Act of which Assange faces 17 counts, refers to as the “Espionage court”).

U.S. attempts to undermine renowned psychiatrist’s testimony

The prosecution then moved to Assange’s mental health and the testimony of Professor Kopelman, the psychiatrist who examined and interviewed Assange and determined he would be at high risk of suicide if his extradition were ordered. The U.S. contends that the defense conflates criteria for breaching Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which says, “No one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,” and those for breaching Section 91 of the UK Extradition Act, which prevent extradition if “the physical or mental condition of the person is such that it would be unjust or oppressive to extradite him.”

As it did in the evidentiary stage in September 2020, the U.S. attempted to elevate the opinion of its own psychiatrist, Dr. Nigel Blackwood. over that of Dr Kopelman. Dr. Blackwood “accepted there was some risk of a suicide attempt linked to extradition but this did not reach a ‘substantial risk’ threshold.” In October 2020, Declassified UK reported that Dr Blackwood “works for an academic institute that is funded by the UK Ministry of Defence and linked to the US Department of Defence.”

The U.S. spent considerable time in the afternoon session repeating its arguments from the evidentiary stage of the proceedings back in September 2020. Lewis reiterated the U.S.’s feeling that Dr. Kopelman misled the court in his first psychiatric report by omitting his awareness that Julian was in a relationship with Stella Moris. In her ruling, Judge Baraitser addressed the issue head-on:

“I did not accept that Professor Kopelman failed in his duty to the court when he did not disclose Ms. Morris’s relationship with Mr. Assange…. Professor Kopelman’s decision to conceal their relationship was misleading and inappropriate in the context of his obligations to the court, but an understandable human response to Ms. Morris’s predicament. He explained that her relationship with Mr. Assange was not yet in the public domain and that she was very concerned about her privacy. After their relationship became public, he had disclosed it in his August 2020 report. In fact, the court had become aware of the true position in April 2020, before it had read the medical evidence or heard evidence on this issue.”

The prosecution attempted to persuade the High Court that if it doesn’t find this renders Kopelman’s testimony inadmissible, it should at least find that it holds much less weight than Baraitser did. The U.S. argument boils down to this question of weight, rather than contestations of fact: which witnesses and statistics and pieces of evidence should be considered more seriously than others. Lewis complained that the judge didn’t adequately explain her reasoning for preferring Kopelman’s testimony.

Defense responds; judge preferred Kopelman

But as Edward Fitzgerald pointed out when responding to the prosecution in the final half hour of today’s session, the judge can’t explain in detail her reasoning for weighing every bit of evidence more than others, and in fact she was quite clear about how she reached her conclusion. “I preferred the expert opinions of Professor Kopelman and Dr. Deeley to those of Dr. Blackwood,” Baraitser wrote. “[Dr. Blackwood’s] summary of the notes was significantly less detailed than the summary provided by Professor Kopelman and he did not appear to have access to all relevant notes.” For example, Dr. Blackwood didn’t even know why Julian was in the healthcare ward at Belmarsh, that ”Mr. Assange was finding it hard to control his thoughts of self-harm and suicide.”

The prosecution argued that the present tense in the phrase barring extradition on the grounds that “the physical or mental condition of the person is such that it would be unjust or oppressive to extradite him” means that only a defendant’s present mental health conditions should be considered, as opposed to how future prospective prison conditions might impact the risk of suicide. But Fitzgerald responded that Dr. Kopelman addressed this as well, finding that the mere ordering of Assange’s extradition would trigger this grave risk, so this was considered an imminent issue rather than a hypothetical.

Court adjourned after Fitzgerald’s point-by-point response to the arguments the U.S. made in court today. Tomorrow, the defense will have the majority of the day to argue its own response to the full government submission. We’ll return at the same time tomorrow.