SEPTEMBER 17, 2020

- See previous daily reports here and a video recap of last week’s proceedings here

- See an overview of USA v. Julian Assange here

- See a thread of live-tweets of today’s hearing here

WikiLeaks’ Iraq War Logs exposed 15,000 civilian casualties

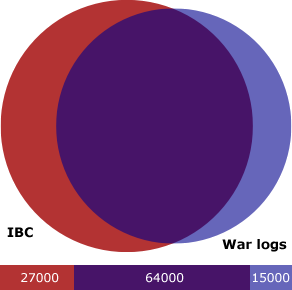

John Sloboda, co-founder of Iraq Body Count, an independent NGO devoted to continuously counting killings civilians in Iraq, testified today about working with Julian Assange and WikiLeaks on the Iraq War Logs, released in October of 2010.

Sloboda started Iraq Body Count to give “dignity to the memory of those killed”,” because knowing how loved ones die is a “fundamental human need,” and to aid in “processes of truth, justice, and reconciliation.”

The Iraq War Logs, a compendium of 400,000 Significant Activity reports filed by the U.S. Army, constituted “the single largest contribution to public knowledge about civilian casualties in Iraq”, Sloboda testified. The logs revealed an estimated 15,000 previously unknown deaths.

Most of these deaths were the results of small incidents, meaning 1-3 deaths at a time, “the kinds of incidents that attract the least reporting” he said in his statement.

Redaction process

WikiLeaks invited Iraq Body Count to join the media partners and given pre-publication access to the material. Assange imposed a “very stringent redaction process” in order to protect named sources from potential harm. Sloboda explained that because the necessary redactions would have taken a team of hundreds to do this manually, an automated process was developed to scan the files and redact every word that wasn’t in a standard English dictionary, to automatically remove any names. Then the files were scanned to remove occupations, like “doctor” or “driver”, so as to further protect identities.

Redacting the logs took “weeks”, Sloboda said, calling it a “painstaking process.”

The other journalists in the partnership wanted to hurry to publication. “There was considerable pressure on Wikileaks because the partners wanted to publish faster,” Sloboda said, but WikiLeaks continuously rejected this pressure, insisting that redactions must take place. Some media partners had redacted a small number of documents by hand and wanted to publish those first, but “Assange and WikiLeaks wanted the entire database to be released together.”

Many people who used the war logs would agree they were over-redacted, Sloboda said, but the agreed stance was to be overcautious first and then to take a closer look afterward, to possibly unredact something if it was agreed it could be revealed.

On the importance of the releases, Sloboda writes in his witness statement that 10 years on, the Iraq War Logs “remain the only source of information regarding many thousands of violent civilian deaths in Iraq between 2004 and 2009,” and it is Iraq Body Count’s position that “civilian casualty data should always be made public.” While the U.S. government often claims that the disclosure could have endangered Iraqi or U.S. lives, it “has never been able to demonstrate that a single individual has been significantly harmed by the release of these data. This is not least because the War Logs were highly redacted prior to their release by Wikileaks.”

“It could well be argued, therefore, that by making this information public Manning and Assange were carrying out a duty on behalf of the victims and the public at large that the US government was failing to carry out.”

Carey Shenkman: Espionage Act is an “extraordinarily broad” political offense

The defense then called Carey Shenkman, an American human rights attorney and constitutional historian who is writing a book on historical analyses of the Espionage Act, to testify by video link from the United States. Shenkman has worked for the late Michael Ratner, President Emeritus at the Center for Constitutional Rights, which advised Assange and WikiLeaks prior to Ratner’s passing.

Shenkman’s witness statement gives a history of the use of the Espionage Act, created in 1917 under President Woodrow Wilson, in what Shenkman refers to as “one of the most politically repressive [periods] in the nation’s history.” The act was used against a range of dissidents, and Shenkman says he provides this history to show how widely it can be used and to show that the act is “extraordinarily broad” and one of the U.S.’s most divisive laws.

Shenkman explained two key points about the law: first, it is written to criminalize the disclosure of not sure “national security information” but all “national defense” information, which means it encompasses even information that isn’t classified, and second, the act does not include a “public interest” defense, meaning defendants can’t argue that disclosures were made to benefit the public.

In 2015, Shenkman wrote about the use of the act against whistleblowers in an article for the Huffington Post, ‘Whistleblowers Have a Human Right to a Public Interest Defense, And Hacktivists Do, Too.”

“Not a single one of those prosecuted has been allowed to argue that their actions served the public good…Whistleblowers cannot argue that their actions had positive effects, known as a “public interest defense.” The United States treats disclosures to the press as acts of spying — no matter what good they lead to.”

Also in 2015, Shenkman and Ratner wrote, ‘CCR to UN: Whistleblower Protections Must Include Publishers Like WikiLeaks and Julian Assange’

“the ultimate effect of prosecuting and censoring publishers is the unacceptable chilling on the free flow of information, rights to access information, and freedom of expression.”

Because of just how controversial the Espionage Act is, Shenkman testified, there has never been a prosecution like the one against Assange.

“There has never, in the century-long history of the Espionage Act, been an indictment of a U.S. publisher under the law for the publication of secrets. Accordingly, there has never been an extraterritorial indictment of a non-U.S. publisher under the Act.”

Therefore, Shenkman told the court, journalists have generally felt comfortable that their activity was protected. This changed briefly in 2010, when the Obama administration began using the Espionage Act against sources and even named journalist James Rosen as an unindicted co-conspirator in an Espionage Act case, and fellow reporters began to get nervous. But Shenkman says, that anxiety was dialed back when then-Attorney General Eric Holder announced, upon his resignation in 2014, that naming Rosen as a co-conspirator in that case was his greatest regret in office.

But the Trump administration’s escalation from prosecuting the sources to prosecuting the publisher has signaled a major shift that carries a widespread chilling effect. Shenkman writes:

“What is now concluded, by journalists and publishers generally, is that any journalist in any country on earth—in fact any person—who conveys secrets that do not conform to the policy positions of the U.S. administration can be shown now to be liable to being charged under the Espionage Act of 1917.”

“Highly politicized prosecution”

On cross-examination, prosecutor Clair Dobbin attempted to get Shenkman to concede that in 2015, he felt that the U.S. still may bring charges against Julian Assange. This is part of the prosecution’s effort with most witnesses to attempt to undermine the 2013 Washington Post article reporting that the Obama Administration would not be bringing Espionage Act charges against Assange. This is a key factor in the extradition proceedings, because the US-UK Extradition Treaty bars extradition for “political offenses”, and a clear decision not to prosecute by one administration followed by a 180º shift to a decision to prosecute by the following administration would appear plainly politicized.

Shenkman testified that he took the 2013 article at face value, that he believed the Obama DOJ had decided not to prosecute. Asked about the investigation into WikiLeaks continuing across administrations, Shenkman said, “oftentimes these things are left to simmer, but ultimately an indictment wasn’t brought.” Furthermore, he argued, if Obama and Holder truly wanted to prosecute, wouldn’t they have been eager to do so? Wouldn’t Obama have wanted to write in his memoirs that he was the one to prosecute WikiLeaks?

Asked again about the ongoing investigation, Shenkman said, “Using the Espionage Act like this is extremely contentious,” something he thought would be an apt assignment for law school students to debate and explore because it’s so contentious.

“I’ve never thought we would see something like [this indictment], he said, adding that most legal scholars agree that this use of the Espionage Act is “truly extraordinary.” Furthermore, he said, the way the charges are framed and the timing of the indictment “really point to a highly politicized prosecution.” He began to comment on the politicized nature of the way the 3 “pure publication” charges are written, but the prosecution stopped him, saying they’d go through the indictment later.

In a long back-and-forth, the prosecution attempted to get Shenkman to comment on agreed legal principles in the U.S. Shenkman repeatedly explained that these are contentious issues dependent on the circumstances.

“Do you agree that a government employee who steals national security or national defense information is not entitled to use the First Amendment as a shield?” Dobbins asked.

“It’s a highly fact-specific inquiry,” Shenkman said, and it “depends on what you mean by ‘steal.” For example, Shenkman noted that the 9th circuit appeals court recently ruled on Edward Snowden’s NSA disclosures, and “they credited Mr Snowden with those disclosures even though he was a government employee accused of stealing these things.”

Shenkman and Dobbin had a similar disagreement over the use of “hacking” — asked, “Are you saying that hacking government databases is protected under the First Amendment?”, Shenkman said he’d have to ask what she means by “hacking”, because the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act doesn’t actually use the term, instead it deals with “exceeding unauthorized access.”

Phrases like “crack a password” and “hack a computer” sound “scary”, Shenkman said, but there are many nuances and interpretations to consider. “So yes I think there are ways the First Amendment could be relevant.”

Failing to get a yes or no answer, Dobbin asked, so shouldn’t these matters be decided in a U.S. court?

Shenkman responded, “No,” saying that his testimony was about the application of the Espionage Act, and whether the way they are written in the indictment against Assange is “political.”

It became clear we would need more than another hour for Shenkman’s cross-examination and closing questions by the defense, so court was adjourned for the day, and Shenkman will return to the stand tomorrow afternoon.