May 20, 2024 – The UK High Court has granted Julian Assange permission to appeal his extradition order, specifically on the grounds that the United States has failed to properly assure the British courts that Assange would get adequate freedom of expression protections if he were extradited.

The appeal permission is narrow but provides the first real chance for the substantive issue of whether the First Amendment would protect Assange can be aired in court. The parties have been given until May 24 to submit a proposed outline for how such an appeal hearing would be argued.

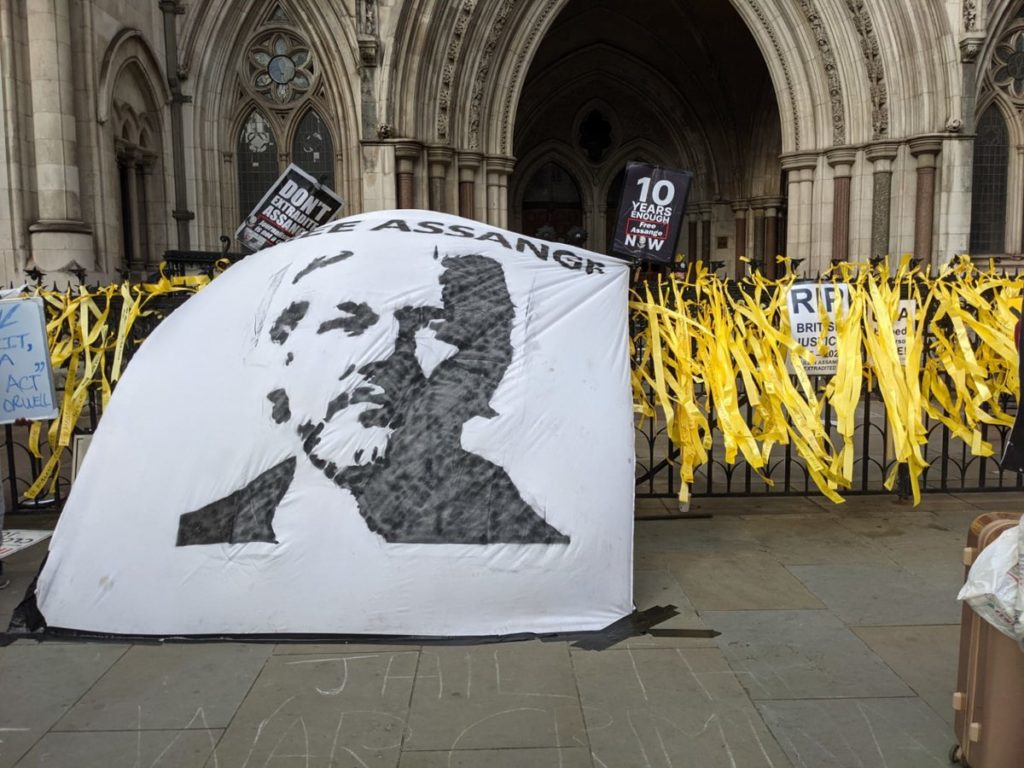

Beginning early this morning, hundreds of supporters gathered outside the Royal Court of Justice, along with free press groups, journalist unions, and other public figures in attendance.

Edward Fitzgerald KC opened the proceedings for the defense by announcing that the defense accepts the U.S. assurance regarding the death penalty, because it is unequivocal and would be binding on U.S. courts — the U.S. simply stated clearly that Assange would not be charged with a death penalty offense.

As to the assurance regarding Julian Assange’s right to assert protections guaranteed under the First Amendment, Fitzgerald maintained it offers no guarantee whatsoever. The assurance given “does not promise that the applicant can rely on the First Amendment. Merely that he can raise and seek to rely on it.”

Furthermore, Fitzgerald argued,

“The court has made a finding on the basis of Mr Kromberg’s statement that ‘concerning any First Amendment challenge, the United States could argue that foreign nationals are not entitled to protection under the First Amendment, at least as it concerns national defense information’”

“The court’s express finding was that ‘If such an argument were to succeed, it would (at least arguably) cause the applicant prejudice on the grounds of his non-US citizenship (and hence, on the grounds of his nationality)’”

There is a wide range of cases in which U.S. prosecutors have given clear, express, and unequivocal assurances when they want to. “We have nothing of that sort here,” Fitzgerald said. “All we have is ‘he may raise and seek to rely on’.” He went on to cite specific promises common to assurances.

“The U.S. states that the so-called assurance is adequate because the judges will take ‘solemn notice’ of it. But the U.S. accepts that the assurance ‘cannot bind the court’ ‘Taking solemn notice’ of an assurance that was expressly stated not to bind the courts cannot operate as a guarantee that the court will apply U.S. law in a way that permits the Applicant to rely on the First Amendment, despite his foreign citizenship.”

Mark Summers KC continued for the defense, warning the court that the U.S. will try to raise that nationality and citizenship are different, a new argument that they should have raised beforehand, and in court, which they did not.

As anticipated by Summers, James Lewis KC for the prosecution argued that the assurance regarding Julian Assange’s First Amendment rights is that Julian will not be discriminated against based on his nationality, but instead on his citizenship. He argued, for the first time, that this is an important distinction.

He claimed that “the applicability of the Applicant’s First Amendment argument requires inter alia the components of (1) conduct on foreign (outside the United States of America) soil; (2) non-US citizenship; and (3) national defense information.”

“Its restriction in scope [of the assurance] is not by reason of his [Julian’s] nationality, but by virtue of the fact that he is a foreigner, carrying out actions on foreign soil,” Lewis argued.

As to the ‘scope’ of the protection, Lewis maintained that “this court has already observed that the counts are of a different nature”, which implies that the First Amendment protections can be selectively applied, depending on the count in question.

He tried to substantiate this argument by saying that Chelsea Manning had no First Amendment protection, so therefore anyone complicit with her would not have First Amendment protection either.

After Lewis concluded, the lawyer for the UK Home Secretary, Ben Watson, addressed the court briefly, only to convey that Home Secretary, who has the final say on extraditions, accepts the diplomatic assurances provided by the United States and says the court should do the same.

Summers returned to address Lewis’s arguments regarding nationality vs citizenship. “Nationality is wider,” he said. “You can be a national without being a citizen, you cannot be a citizen without nationality.”

“In addition to being a non-US citizen Mr Assange is a non-US national as well. Whatever the distinction may be, and we don’t accept that there is any… it has no bearing whatsoever”

“The exclusionary rule has a number of limbs to it… Mr Lewis said in terms he will be excluded because he is a foreigner, carrying out acts on foreign soil concerning national security… Well, he is being excluded in part because he is a foreigner [as opposed to if he were a US citizen]”

Concerning the question of scope, Summers concluded that it’s not arguable that it is allowed to violate people’s rights under certain conditions. The protection is an absolute. If Assange would be discriminated against at trial, the extradition must be barred.

The proceedings were completed with the address from Fitzgerald, who stressed once more the wording of the assurance: “He will be permitted to raise and seek to rely on it.” This is not the same as granting Mr Assange the right to raise First Amendment arguments, Fitzgerald concluded.

The proceedings adjourned for 20 minutes, after which the judges returned with a ruling.

The High Court ruled that it is unsatisfied with U.S. assurances and granted Julian Assange leave to appeal on grounds 4 (violation of free speech rights) and 5 (prejudiced at trial due to nationality). The other ground (related to the death penalty) has been rejected.

The lawyers will have until 2pm on May 24 to file an agreed case outline.

Free press organizations around the world welcomed the High Court’s decision, stressing once more the prosecution’s disastrous implications for press freedom and calling on the U.S. government to finally end it.